As Time Warner’s metered broadband plans are currently shelved, awaiting a more palatable consumer climate, we have time to examine why broadband providers suddenly feel compelled to eliminate the flat-rate, all-you-can-eat pricing model. Metered Internet service is hardly a new idea; early services like AOL and Compuserve were metered, but, with competition from thousands of independent ISPs, all-you-can-eat plans ultimately won out and users have enjoyed flat-rate unlimited service ever since. So, why now do some broadband providers want to return to a failed pricing model that users rejected long ago?

According to Time Warner, usage caps and metered pricing are the “fair” way to charge for broadband service. Why should light Internet users pay just as much as heavy users that download 100 times more data? Or as Time Warner COO Landel Hobbs asked, “When you go to lunch with a friend, do you split the bill in half if he gets the steak and you have a salad?” What Time Warner and Hobbs are implying, of course, is that their costs are based on usage and that providing service to heavy users is more expensive than for light users.

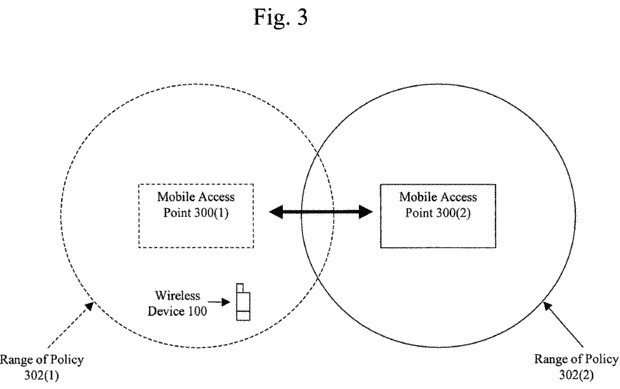

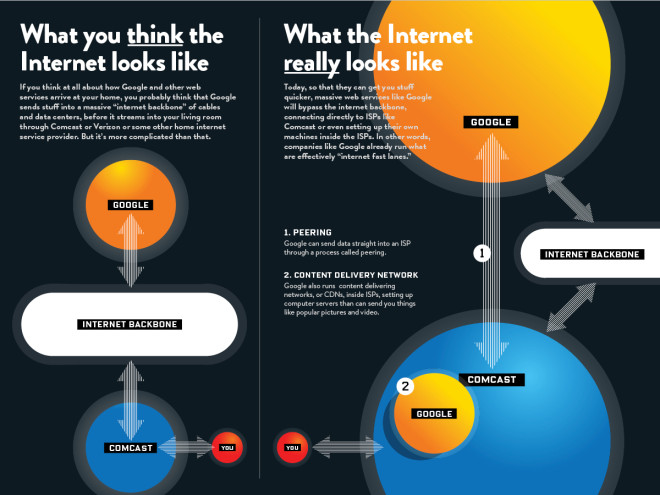

Time Warner’s fairness justification seems intuitive and sounds good, but there’s a problem with its premise. Broadband providers’ costs are not directly tied to usage. A user could download 10GB of movies today and turn off her computer tomorrow, and Time Warner’s costs for those two days wouldn’t be materially different. This is because broadband providers’ infrastructure and peering costs are largely fixed. Once these expenses have been sunk, the cost of providing service to both heavy and light users is nominal. In this regard, Time Warner is really selling access to its network, rather than gigabytes. So, I think Hobbs’s question would be more accurate if he asked, “When you go to a movie with a friend, do you split the bill in half if he watches every minute and you take a nap?” Of course you do because you’re paying for admission and how you choose to use that access is of no consequence to the theater’s costs or ticket prices.

Instead, metered pricing plans and usage caps are a strategy intended to salvage diminishing cable revenues by forcing users to use less Internet. Users have been watching increasing amounts of video online, with some abandoning their cable service altogether in favor of broadband (an effect that has been sped by the struggling economy). This presents an obvious dilemma for broadband providers that also offer a cable product, like Time Warner: as online video watching goes up, the revenue-generating cable usage goes down. Online video is bad for business because a cable company directly profits from its cable content through advertising, pay-per-view and video-on-demand, but can’t profit off Internet content. The fact is that Time Warner is offering competing products and the company has a vested interest in cable video prevailing over Internet video. Time Warner introduced metered pricing and usage caps to make its customers turn off their computers and pick up the remote.

The public backlash that forced Time Warner to (temporarily) acquiesce demonstrated that Internet users don’t want to return to metered pricing, but Time Warner already knew that. The company thought it could get away with introducing a hugely unpopular pricing scheme because it knew that its customers have very few broadband options. The vast majority of users are served by a phone company and cable company duopoly, which can hardly be said to be a free and functioning market.

Time Warner targeted cities for metered pricing and caps where it knew that its customers wouldn’t cancel their service. At the time the plan was announced, each of the four cities (Austin, San Antonio, Greensboro and Rochester) were served by phone companies (AT&T and Frontier) that were themselves in the process of implementing usage caps and metered pricing. Time Warner knew that the only other broadband option available in these cities was intent on doing the same thing and that its customers had nowhere else to go for unlimited service.

This is exactly the type of behavior that happens in unregulated monopoly markets (and duopoly markets are little better as they inevitably tend towards implicit collusion). Without sufficient competition, broadband providers have no incentive to improve their product. This is why America’s broadband access and speeds lag embarrassingly far behind Asian and European countries that have functioning broadband markets with multiple providers. Only when we have a broadband market with more providers and some semblance of competition will we see an end to unfair and unpopular practices, like cable-revenue protecting usage caps.

06/01/09 UPDATE: Last week, Time Warner CEO Glenn Britt essentially admitted that the competitive threat of online video to traditional cable is the driving force behind the company’s capped and metered pricing model. Mr. Britt told investors, “If, at an extreme, you could get all of the programming you get over cable for free on the Internet, over time people will stop buying (TV).” Unfortunately, the public collateral damage of forcing customers to use less Internet and more TV is not a consideration in Time Warner’s plans. The Internet is a medium for free expression and a facilitator of unrestricted communication, education, and commerce. Television simply is not.

Matthew Henry is an EFFA board member and a partner at McCollough|Henry, PC